Vote "No" on Virginia's constitutional amendments

###

In an exciting general election season, it’s easy to overlook the dreary matter of amendment questions. Virginia voters must approve all amendments, and this year, they’re being asked about two of them.

One needlessly jams a piece of sound extant labor law into a place where it doesn’t belong, and the other is an ill-considered tax scheme that doesn’t serve meaningful policy objectives.

Both proposed amendments for 2016 deserve to be soundly rejected at the ballot box.

Amending our constitution is a big deal

As provided for in Article XII of the Constitution of Virginia, amending the document requires approval by a majority of both the House of Delegates and the Senate in two separate sessions with a House of Delegates election between them, followed by a voter referendum. Constitutional amendments are one of the few ballot issues most Virginia voters see with any frequency. Unlike states with more populist traditions that allow citizen groups to propose statewide ballot initiatives, only the General Assembly can put matters to such a referendum, and it rarely chooses to do so.

Let’s break this process down to how these amendments wound up in front of voters in 2016:

- In 2014, a majority of members of the House of Delegates and the Senate voted for each new amendment.

- The Constitution requires an intervening House of Delegates election, which we have every two years, before amendments go back for their second approval. We held this in 2015.

- Following that election, the 2016 General Assembly was presented the same measures again. A majority of members of the House of Delegates and the Senate voted in favor of them again.

- The amendments were then ordered to be placed on the ballots for voter approval in the November General Election. If a majority of voters vote “Yes” on the amendments, they will become part of the Constitution of Virginia.

If these amendments are approved, it will be the conclusion of a three year process, which is as short of a process as is possible under the constitution. So if later we decide these things we put into the Constitution of Virginia aren’t a good fit for us anymore and we’d like to change them, how do we do that?

Repealing amendments to the constitution, or even changing the wording of them, is a form of amending the constitution. So yes, you guessed right: by putting these matters into the constitution, we’ve moved them from matters we can tweak, adjust, or drop altogether in one General Assembly session to matters that take a minimum of three years to resolve.

Bearing the ardor of approving amendments, they should address matters that can only be resolved through constitutional change, and represent extraordinarily sound, well-designed policy.

Neither of the 2016 amendments rises to that standard.

Question One is already properly defined by statute

Should Article I of the Constitution of Virginia be amended to prohibit any agreement or combination between an employer and a labor union or labor organization whereby (i) nonmembers of the union or organization are denied the right to work for the employer, (ii) membership to the union or organization is made a condition of employment or continuation of employment by such employer, or (iii) the union or organization acquires an employment monopoly in any such enterprise?

The so-called “Right-to-Work Amendment” doesn’t belong in the Constitution.

The Code of Virginia already has an entire article devoted to spelling out the commonwealth’s position that union membership or non-membership shouldn’t be a condition of employment. This article was adopted in 1970, and to date has survived the scrutiny of the courts as consistent with the constitution.

The assessment of whether the amendment proposed by Q1 is a good idea or not can actually stop with just that one fact: the statute is on the books and it’s worked as the General Assembly intended for nearly half a century. The only reason to embed this language in the constitution would be to make altering it more difficult.

But the proposed amendment actually takes § 40.1 Article 3 even further. While current statute holds that companies can’t make employees join or not join unions, the amendment would merely restrict companies from mandating union membership for employees. That sounds like a dweeby quibble, but it’s a shift from decades of employment policy that favors corporate bodies to the disadvantage of employees.

Whether you think “Right-to-Work” is good policy or not, the Virginia Constitution is the wrong place for it to be defined. Turn this one down.

Question Two helps the wrong people

Shall the Constitution of Virginia be amended to allow the General Assembly to provide an option to the localities to exempt from taxation the real property of the surviving spouse of any law-enforcement officer, firefighter, search and rescue personnel, or emergency medical services personnel who was killed in the line of duty, where the surviving spouse occupies the real property as his or her principal place of residence and has not remarried?

The second amendment before voters is the latest in a string of flawed amendments that would create a tricky, caveat-loaded benefit for a tiny number of Virginians. The General Assembly, in advancing this measure, has decided that the best salve for grief is, of all things, property tax relief. The intent is probably OK, but the strictures that come with this amendment ensure it will help few Virginians, and those it does offer relief to aren’t the ones who need it most.

For a person to receive a property tax exemption under the Q2 amendment, they’d have to meet all of these qualifications:

- Have been legally married to an emergency service worker – specifically, “law-enforcement officer, firefighter, search and rescue personnel, or emergency medical services personnel” – who died while doing their job

- Own their own home

- Live in a county or city whose governing body has decided to offer a property tax exemption to spouses of emergency service workers who died while doing their job

- Remain unmarried if they wish to continue receiving a property tax exemption

With me still? Cool. With that in mind, what’s the purpose of this amendment?

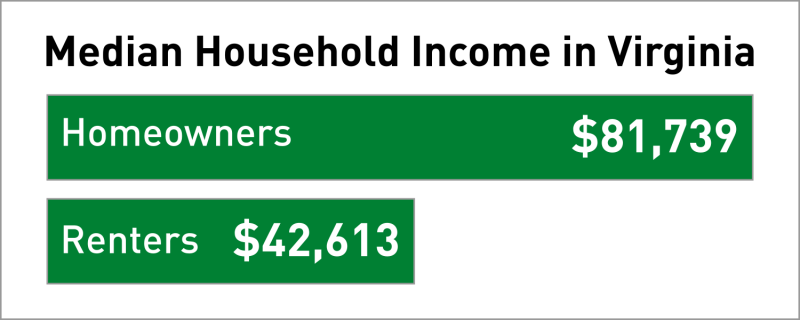

If the purpose is to help partners financially after a sudden loss, then this measure is seriously mistargeted by offering a tax break to those least likely to need one. The median household income for homeowners in Virginia is $81,739, nearly twice the MHI of renter-occupied households, $42,613.

By that measure alone, a property tax exemption is the wrong tool to help widows and widowers. But even providing this benefit to spouses comes with issues, as being married in the first place tracks with substantially higher individual and household income. Marriage also comes with vast ethnic disparities. Where 75% of white adults in Virginia are currently married, just 33% of black adults are.

Statistically speaking then, this measure would largely benefit higher-income whites. Does that sound like the kind of benefit that we’d like to permanently embed in our constitution?

Not even mentioning the perverseness of asking widowers who’ve found a new partner to check in with a tax professional to determine if they should claim the tax benefits of marrying them or the tax benefits of the property tax exemption that they would forfeit by choosing to move on from their grief and remarry.

That’s just cruel.

Question Two seems like a sensible act of state compassion on its face, but its structurally flawed design means it can’t provide one bit of assistance to many of the neediest families that lose a loved one in service. Vote no on this and ask the General Assembly to design something better.

Always default to ”no” on constitutional amendment votes

Constitutions are meant to be compact. They define the powers and limits of governmental authority and the essential rights of citizens, and are supreme over all statutory laws and regulations. As such, amending Virginia’s constitution should only be done with extreme scrutiny and obvious need.

Constitutional amendments are one of the very few matters of policy that most Virginia voters will ever vote on directly. Don’t be afraid to exercise your veto power over them. If they’re really important, the General Assembly can always go back to the drawing board and rewrite them or explain them better, but if voters approve putting bad policy into the constitution, as they did in approving the so-called “Marriage Amendment” in 2006, the fix isn’t nearly as simple.

Happy voting, Virginia!