Richmond and Henrico: A Tale of Two Revenue Streams

You could almost write the story arc in Mad Lib format by now: Richmond Mayor Dwight C. Jones proposes a thing. The Internet Comments Sectiontariat, knowing that the administration proposing the thing is that of Mayor Dwight C. Jones, not exactly the most popular executive in Richmond’s history at this point, reacts with universal condemnation and horror, certain that whatever the thing is, it is probably as bad as building three new Redskins Training Camps inside of 6th Street Marketplace.

Here’s the thing though: when the administration says Richmond’s government can’t afford to do the things citizens want it to without collecting more revenue, and that taxes and fees may need to rise, that didn’t come from nowhere. A quick and dirty comparison of the tax take between the City of Richmond and the neighboring county of Henrico offers a really easily overlooked possibility: maybe Richmond really just doesn’t take in enough money.

Let’s start with by far the largest source of revenue: local property taxes. In the current budget cycle, Richmond expects to bring in $250,225,128 in property tax revenue for its 214,114 citizens — $1,169 per capita. Henrico is anticipating $408,950,000 total for the 318,611 county dwellers, which makes $1,284 in property tax per capita, nearly 10% more than Richmond.

What gives? Even though Henrico’s property tax rate of $0.87/100 is substantially lower than Richmond’s $1.20/100, the county’s taxable property value is about $35.6 billion to Richmond’s $20 billion. With nearly 80% more value to collect on, the county collects more revenue even with a 35% lower tax rate.

So what would put the two in parity? To oversimplify, Richmond could just about match Henrico’s property tax revenue per capita under two scenarios tackling the equation from either end. If Richmond’s taxable property value increased by about 15%, or $2.9 billion, that would just about do it without moving the current tax rate. The city could also raise the real property levy to $1.37/100 at the current book value. That’s a 15% increase, but just about what Petersburg is currently collecting.

Since raising property taxes is pretty unpopular, this should lend a little clarity to why the Jones administration has put such a strong emphasis on economic development, even if there’s a lot of (legitimate) disagreement about some of the ways they’ve pursued that goal.

What’s going on here then? Surely property taxes make up a bigger slice of the pie in Henrico, and that explains the disparity?

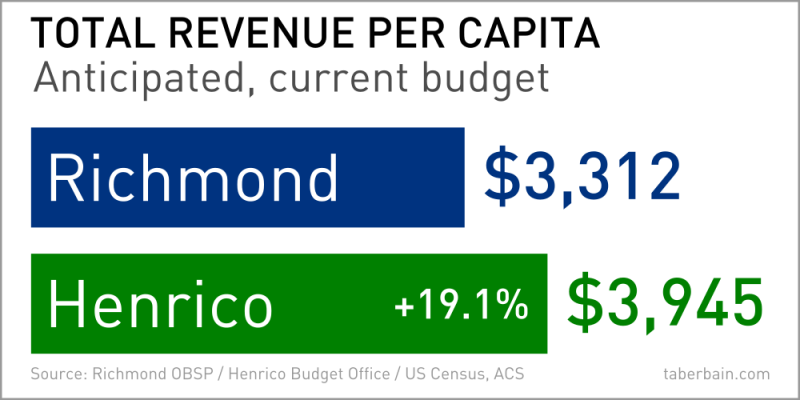

Nope. When considering all revenue, the gap is even more vast. Richmond is anticipating $709,152,771, and Henrico is looking for $1,256,906,591. On a per capita basis, that means Richmond is collecting $3,312 in total revenue for every citizen, while Henrico is collecting $3,945 — about 19% more.

When we talk about our priorities for future local government budgeting, we have two really unfortunate and hugely unproductive instincts in Richmond:

- To assume there are simply vast inefficiencies lurking in city administration that, if someone just had the guts to go in and eliminate, we could afford to do anything we wanted, and

- To turn every discussion about future budgeting into a referendum on past budgeting — and I know you, Richmond, I know you have a project or expenditure on the tip of your tongue that you want to fume about right this second — on the premise that if we just hadn’t spent some money on whatever that thing was, we would be able to afford whatever the thing was we want to do now.

You’ve gotta let those go, y’all. Nobody is going to find a way to trim 20%, or even 10%, from the city’s budget without completely crippling even the most basic public services, and we can’t take back money that’s already been spent to put towards something else.

Focus on what’s real and what’s right now. Richmonders want their government to spend more money on schools like Henrico, but Richmond’s government doesn’t bring in as much revenue per person, and its debt capacity for capital projects is tapped out.

Sometimes, it’s just this obvious: we can’t afford to do what we want because we just don’t have enough money.